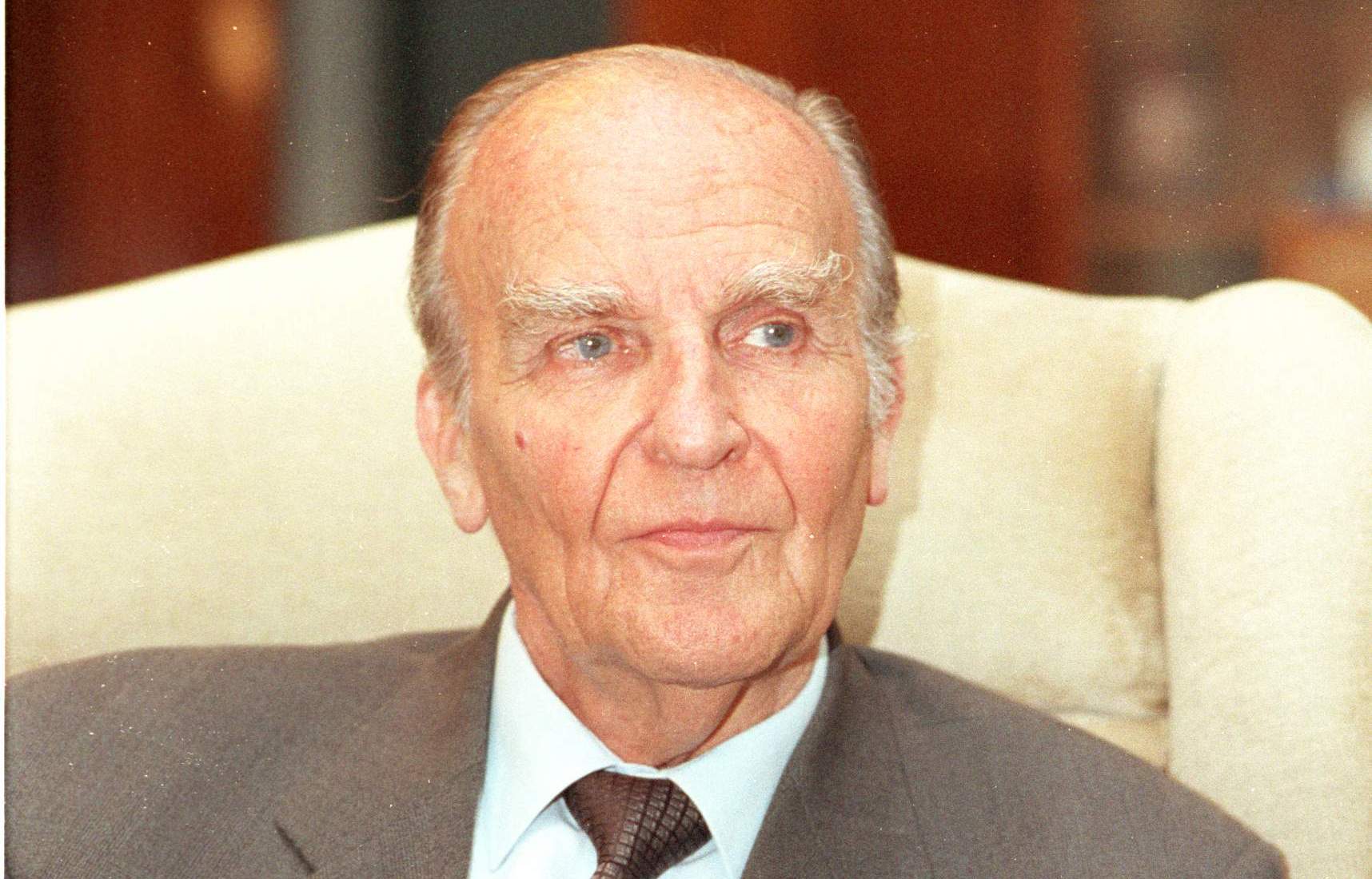

BOSNIA on the historical border a lecture given at the Examination Schools, Oxford on 2 April 2001 by HE Alija Izetbegovic Former President of Bosnia-Herzegovina

Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies

Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, dear friends: I was very honoured when I was invited by Dr Nizami to speak at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. I was glad that this was to take place at such an important cultural centre as Oxford, and at such an important time as the beginning of the new millennium.

Today I visited the Centre for Islamic Studies. Although I have known a great deal about its activities, I was impressed to hear from Dr Nizami about some future projects. This Centre is for the benefit of the Muslims in Europe and the world, and indeed for the benefit of all others. I want to extend my full support and ask all those who can to do so.

I have decided to speak about my country, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is a challenging topic, for to speak about Bosnia and Herzegovina means to speak about two worlds – East and West – and about their encounters, which have been both fruitful and destructive. The line that separates (or joins, if you will) those two worlds has run during many centuries, at times eastwards, at times

westwards, through Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Bosnia, great powers and great religions in the history of Europe – the Roman Empire, Charlemagne’s empire, the Ottoman and the AustroHungarian empires, and the religions of Western and Eastern Christianity, Judaism, and Islam – have overlapped and merged. The product of these clashes and influences is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multicultural Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country that in this respect is a rarity in the world.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, a small country of 51,000 square kilometers, is situated in the western part of the Balkan peninsula roughly between the latitudes of 42˚ and 45˚N and the longitudes of 15˚ and 19˚E. It marches to the north and west with the Republic of Croatia, and to the east and south with Serbia and Montenegro. According to the 1991 census, Bosnia had a population of some 4,377,000, of which 44 per cent were Bosniacs (predominantly Muslim), 17.4 per cent Croats (predominantly Catholic), 31.2 per cent Serbs (predominantly Orthodox Christian), and 7.7 per cent others (mainly of mixed religious background).

The present-day political borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina were established during the eighteenth and nineteenth century by a series of peace accords and conventions but, as ageopolitical entity, Bosnia has an almost unbroken history from the mid-mediaeval period to the present. From 1180 to 1463 Bosnia was an independent kingdom; from 1580 to 1878 it was so called ayalet (a term designating the largest territorial unit in the Turkish empire); from 1878 to 1918 it was a ‘crown land’ within the Austro-Hungarian Empire; and from 1945 to 1992 it was one of the federal republics of Yugoslavia. Since 1992 Bosnia and Herzegovina has been an

independent state and a member of the United Nations.

The history of Bosnia is a history of struggle for its own identity and independent position on the dividing line between two worlds. In the Middle Ages that desire to belong neither to East nor West, or to belong to both, is well illustrated by the phenomenon known as Bogumilism or the ‘Bosnian Church’. The specific Bosnian Church or Bosnian heresy was an expression of the resistance of Bosnia and the ‘Good Bosnians’ to the rulers of the Christian church, both the Byzantine, in Constantinople, and the Roman as well.

The heretical movement that was to find a firm foothold in Bosnia arose in the East, and reached Macedonia via the Bosporus in the mid-tenth century. Its founder, the priest Bogumil, taught that there were two divinities, two principles – the principle of good and the principle of evil – God and Satan. The Bogumils rejected the sacraments, liturgy, the church, the cross, statues, and icons.

Hostility between the Christian East and West reached a peak when the Crusaders seized Constantinople in 1204 and founded their Latin empire. After six wars of the Crusades, of which five were failures, discontent began to foment among the common people. Instead of the rapid victory over the so-called ‘unbelievers’ that the Pope had promised them, there had been defeat after defeat. Instead of concord between people in the Christian world, there was discord and dissension; instead of rich plunder, there were casualties and misery.

Bosnia, which was one of the heartlands of the heresy, lay on the borders between the Eastern and the Western churches. Successive Popes sought to reinforce their positions on that dividing line. Along with this ecclesiastical confrontation, the interests of various secular powers intersected in Bosnia, in particular those of Hungary and Byzantium. The Bosnian heresy was the expression of both aspects of resistance, the spiritual and the political. This united Popes and kings against Bosnia. In 1200, Pope Innocent III invited the Hungarian King Emerik to launch a war against the Bosnian Ban Kulin, and sent his own chaplain, Ivan Kasamarin, to persuade the

most prominent Bogumil leaders to renounce their teachings and recognize the supreme authority of the Roman church. They did so in Bilino Polje in 1203, but it seems that their repentance was not sincere, since the following two hundred years witnessed a series of crusading wars against Bosnia, most of them unsuccessful. The first was launched by Pope Gregory IX in 1234, followed by the Hungarian King Ludovig in 1363, and then by King Zigmund in 1408.

The Bosnian Church was not extinguished; it remained an important factor in the defence of the country against external attack. It was only when the Bosnian King Tomas (1443-61) was faced with the Turkish threat that he began to show sympathies with the Vatican. When Bosnia came under Turkish rule, in 1463, the Bogumil heresy disappeared, and most of the Bosnian Church’s followers adopted Islam.

Bosnia remained under Turkish rule for more than four hundred years. The Islamization of the greater part of the population, which was a gradual process, is the most marked and most important characteristic of the New Age history of Bosnia.

It was when Turkish rule began that Orthodox priests and congregations began to be mentioned for the first time, and certain Orthodox monasteries were referred to as early as the sixteenth century (in Tavna, Lomnica, Paprača, and Ozren). The Franciscans began to be active in Bosnia from the mid-fourteenth century, and in 1463, in Fojnica, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror

signed the famous Ahd-nama or Letter of Covenant, which guaranteed freedom of action to the Franciscans in Bosnia.

In the mid-sixteenth century, with the approval of the Turkish authorities, a large number of Jews came to Bosnia after their expulsion from Spain, along with the Muslims, following the fall of Granada in 1492. The Albanian priest Peter Masarechi states, in his account dating from 1624, that there were 150,000 Catholics, 75,000 Orthodox, and 450,000 Muslims living in Bosnia at that time. There is reliable evidence of the existence of a large Jewish community as well, although Masarechi does not give the number of Jews. Bosnia thus became one of the few countries in which the adherents of four religions live intermingled, a true Abraham’s Ecumena.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the Bosnian Muslims defended Bosnia against Austria, but also against Ottomans, because at the same time there arose a separatist tendency among the Bosnian Muslims in regard to Istanbul. They demanded autonomy for Bosnia, and strongly opposed the reforms of Selim III (1789B1809). This resistance was to cease only with the victory of Sultan Mahmud over Husein-beg Gradašćević, in 1832. In 1737, the Bosnian army defeated the Austro-Hungarian army in a battle near Banja Luka,

after which there were no attacks by foreign armies on Bosnia for fifty years; but in 1788 another war broke out between Turkey on the one hand and Austria and Russia on the other. The Austrian Emperor Joseph II and the Russian Empress Catherine the Great came to an agreement to seize the Balkans from the Turks and divide the region between their two empires. The division of geopolitical interests in the Balkans was to lead, ultimately, to the Austrian occupation of Bosnia in 1878. Thus began the western domination of Bosnia that lasts to this day. First was Austria, which formally annexed Bosnia in 1908. After the First World War, Bosnia became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which until 1943 was a monarchy under Serb domination. For the following almost fifty years, Bosnia was a republic under Communist rule. When all this came to an end, and Bosnia proclaimed its independence in 1992, all the veils fell, and the country was seen in its bare relief: three nations, or perhaps more accurately three religions – Islam, Catholicism, and Serbian Orthodoxy. There was almost no one left of the fourth, the Jews: they had been exterminated by people who came from the heart of Europe, in the war years of 1941 and 1942. There remained only a small community of a few thousand, regarded with well-merited respect.

The major upheavals resulting from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc shook Yugoslavia, which itself straddled the Great Divide. Yugoslavia disintegrated into its basic components of which it was composed. The key country, linking all these different componentsin one, was the multinational and multicultural Bosnia and Herzegovina. The forces that destroyed Yugoslavia from within attempted to do the same to Bosnia. The country was attackedby aggressor forces from the east (in 1992) and then from the west (in 1993). Bosnia mounted a desperate defence, at the core of which were the Bosnian Muslims. The role that was played in the defence of mediaeval Bosnia by the ‘Bosnian Church’ was now played by Islam, as the spiritual bulwark of the majority nation, albeit of course in wholly different historical circumstances.

The Serbian national plan, defined in the nineteenth century, envisaged a Serbia extending as far as Karlobag in Croatia – that is, covering the whole of Bosnia. The Croatian national plan saw ‘Croatia to the Drina’, again covering the whole of Bosnia, but from the other direction. Milošević and Tudman are merely the symbols of this new confrontation in a different historical context. The decisive resistance of Bosnia demonstrated that the country is rooted in history and cannot be destroyed even by upheavals of major intensity, but the human and material cost of the war was appalling: 230,000 people killed, two million forced out of their homes, thousandsof towns and villages razed to the ground. Multi-ethnic Bosnia was seriously wounded, but she survived.

When the war came to an end and the public began to forget what caused it and how it began, doubts about the nature of the conflict were skilfully aroused: was it a case of external aggression, or was it a civil war between ‘three warring peoples’? The aggressors and their local accomplices sought to prove that it was a civil war, and proving it to be a civil war also means proving that the idea of Bosnia is dead.

The question of the nature of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina is of major importance, so permit me to cite some facts in extenso:

The UN Security Council adopted Resolution 752 as early as 15 May 1992, demanding ‘an immediate cessation of all external involvement in Bosnia and Herzegovina, including units of the Yugoslav Army and of the Croatian Army’ (operative paragraph 3 of the Resolution). Since the Belgrade regime did not comply with the demands of Resolution 752, the Security Council repeated them in Resolution 757, of 30 May 1992, and imposed sanctions against Serbia and Montenegro.

In operative paragraph 5 of Resolution 787, of 16 December 1992, the UN Security Council demanded that neighbour countries cease infiltrating para-military groups into Bosnia and Herzegovina, drawing attention this time to units from the army of neighbouring Croatia. Resolution 47/121 of 8 December 1992, titled ‘The Situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, explicitly uses the word aggression. Expressing its dismay that the Security Council sanctions had had no effect, the UN General Assembly accused the Yugoslav Army of ‘direct and indirect support for acts of aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina’, and in operative paragraph 2, the Resolution ‘strongly condemns Serbia, Montenegro and Serbian forces in the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina for violations of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina and for conduct contrary to the Resolutions of the Security Council, the UN General Assembly and the London Peace Agreement of 25 August 1992’. In paragraph 3 the UN General Assembly demands that ‘Serbia and Montenegro cease their acts of aggression and hostility and that they comply wholly and unconditionally with the relevant Resolutions of the Security Council’. In paragraph 7 the General Assembly calls on the Security Council to ‘use all available means to preserve and establish the sovereignty, territorial integrity and unity of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina’. This demand is repeated in UN Security Council Resolutions 819, of 16 April 1993, and 838, of 10 June 1993, and in the presidential statements of 24 April 1992 and 17 March 1993.

UN General Assembly Resolution 48/88, of 20 December 1993, entitled ‘The Situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, notes that the aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina is continuing and calls on the Security Council to implement Resolution 838, of 10 June 1993, without delay. As a result of the hesitation of the great powers, the United Nations Resolutions were not implemented, and there was no military intervention to prevent the genocide, but it was repeatedly noted that this was a case of aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina. Muslim countries, without exception, supported the adoption of resolutions condemning the aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in some cases initiated them. The statements made by representatives of western countries leave no doubt, either, of the nature of the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. When Resolution 757, of 30 May 1992, was adopted, the statements

such as the following were heard:

A representative of the United States of America: ‘The aggression of the Serbian regime and its military forces against Bosnia and Herzegovina is a threat to international peace and security, and a serious challenge to the values and principles on which the Helsinki Final Act, the Paris Charter, and the Charter of the United Nations are based.’

The Russian Federation: ‘Belgrade has ignored good advice and warnings and has not brought its conduct into conformity with the demands of the international community. In this way it is itself the cause of the United Nations sanctions. In voting for sanctions, Russia is fulfilling its obligations as a permanent member of the Security Council for the maintenance of international law and order.’

France: ‘The European Union and its member countries have already adopted a series of measures against Yugoslavia, and called upon the Security Council to take similar action.’ Great Britain: ‘There is in fact no doubt where the chief responsibility lies: with the authorities, both civil and military, in Belgrade. This cannot be covered up; they cannot prove that they have no connection with what is happening in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Multi-barrelled rocket launchers can’t be found in village barns. They come from the depots of the Yugoslav Peoples’ Army.’ Et cetera, et cetera.

The Hague Tribunal, passing sentence on indictments for war crimes, has so far confirmed in three cases (the Tadić, Aleksovski, and Kordić) that the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina was an international conflict, and therefore a case of aggression.

It is true that common living in Bosnia was characterized by ‘its terrible ambivalence’, as KarlJoseph Kuschel calls it, with the theologian Hans Küng, currently the greatest exponent of interreligious dialogue in the world. This ‘ambivalence’ has always raised once again the question whether Bosnia is possible. But did not sceptics once raise the question of whether Europe was possible? Immediately after the Second World War, when Denis de Rougemont called upon Europe to unite, his appeal was met with derision. But only forty years later, this unity is becoming a reality, and what is being created before our very eyes is one of the most significant

events of the twentieth century.

My good friend the Catholic theologian and writer Fra Petar Andelović, receiving the Human Rights Award (in Bonn on 9 June 1997), said, ‘The name Bosnia, and Bosnian-hood, is not a concept of national or territorial order. It is primarily, and above all, the mark of a civilization process that has been taking place through historical changes and political events throughout an entire millennium.’ And to the observation by a journalist that Bosnia is currently the scene of conflicts between peoples, ideas, religions, and cultures, he retorted almost angrily, ‘Bosnia has only been a place of conflict for a few years, and those were externally devised conflicts. Bosnia has otherwise always been a place of encounter of peoples, religions and customs, and this makes her unusual, interesting and great, and as such there can be no death for her, for if she dies, it will be the death of an example of how people can live and overcome all the threats of times to come.’

The prerequisite for Bosnia is not homogenization, some kind of new melting pot in which a homogeneous Bosnian nation would be created from today’s Serbs, Croats, Bosniacs, and others. America today is an example of a relatively harmonious multi-ethnic community, but in the recent census, 83 per cent of Americans declared themselves as having some ethnic identification, and only 6 per cent declared themselves as Americans and nothing else. America has remained a pluralist state in the ethnic sense, but this has not prevented her from also being a stable multiethnic community.

Both Europe and America, however, have gone through long periods of their own ambivalence. The two greatest horrors of the twentieth century – fascism and bolshevism – are European inventions. Throughout its history, Europe has shown a great talent for dictatorships and violence, while American Christianity was until recently infected with racism: even by the midcentury, many churches still had the inscription that only the whites were allowed to enter.

The century that is just behind us has been called by many, with justification, a century of violence: two great wars and numerous smaller ones, in which millions of lives have been lost, and which have seen concentration camps, anti-Semitism, and show political trials. It was only in mid-century and in the second half of the century that signs of hope emerged: the Charter of the United Nations, human rights conventions, the abolition of race restrictions in America, the Helsinki Final Act and its so-called Third Basket of human rights, and so on. The truth is that the dark shadow of events in the Balkans falls across these hopes, but the positive processes are of

global significance.

And between the three great religions, changes are taking place. In 1965, Pope John Paul II visited Morocco and addressed more than 80,000 young Muslims on the subject of ‘our common God of Abraham’, and the following year he visited the synagogue in Rome. It was the first time in history that the leader of the Catholic Church has crossed the threshold of a Jewish place of worship, an act which meant extending a hand to the people that for twenty centuries had been accused of the murder of Jesus Christ.

Many people ask me whether I am optimist about the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I usually answer: Yes, I am. A long way has been passed: freedom of movement has been established in the whole country, refugees are returning to their homes, multi-ethnic police and multi-ethnic border services are being established, and Bosnia and Herzegovina is gradually becoming integral part of Europe. These processes are slow indeed, but the direction is right, and the whole world supports them. Just as I was finishing this, the UN Security Council, debating the current crisis in Bosnia, once again supported the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnia, a country on the Great Divide, is continuing to develop as a multinational and multicultural community in a world that is also a patchwork of races, peoples, religions, and cultures.

Finally, I believe God Himself likes diversity. The dilemma – a monochrome or a polychrome world – is resolved by the Holy Qur’ān, in Sūrat al-Mā’ida: ‘If God had willed, He would have made you one nation.’ Obviously, He did not so will. Let us therefore be proud of what we are and offer one another mutual respect.

https://akos.ba/a-lecture-given-by-alija-izetbegovic-at-oxford-in-2001/